Boreal Chorus frogPseudacris maculata

|

* Older literature and some current sources refer to this species as the Western Chorus Frog (P. triseriata)

General Distribution: Widely distributed from north and west of the Great Lakes to the Northwest Territories in Canada (IUCN, 2013), south through portions of the Great Basin to the Mogollon Rim of Arizona and New Mexico, and east to Missouri and Illinois (Moriarty and Cannatella, 2004; Lemmon et al., 2007).

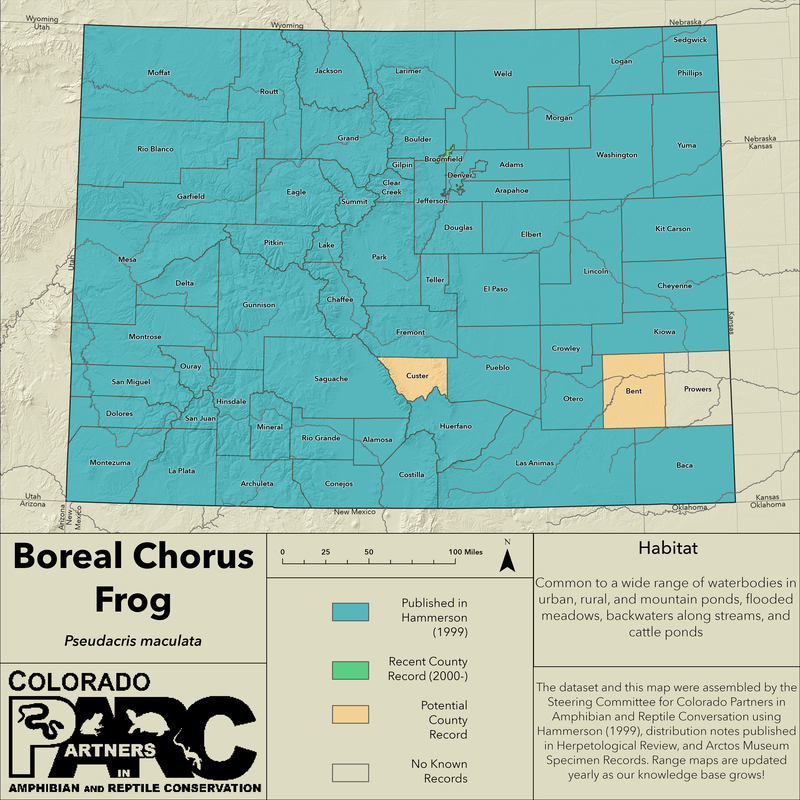

Colorado Distribution: Boreal chorus frogs can be found throughout much of the state. Occurrence becomes patchier to the southeast corner of the state (after Hammerson 1999, Shipley & Reading 2006, and Colorado Parks & Wildlife).

Conservation Status: Designated as a Non-game Species in Colorado. Please click here for Colorado regulations regarding this species (see Article I, specifically number 6). NatureServe rank: G5 (Globally Secure), S5 (State Secure). General threats to conservation include habitat loss and fragmentation along with introduction of invasive fish and bullfrogs.

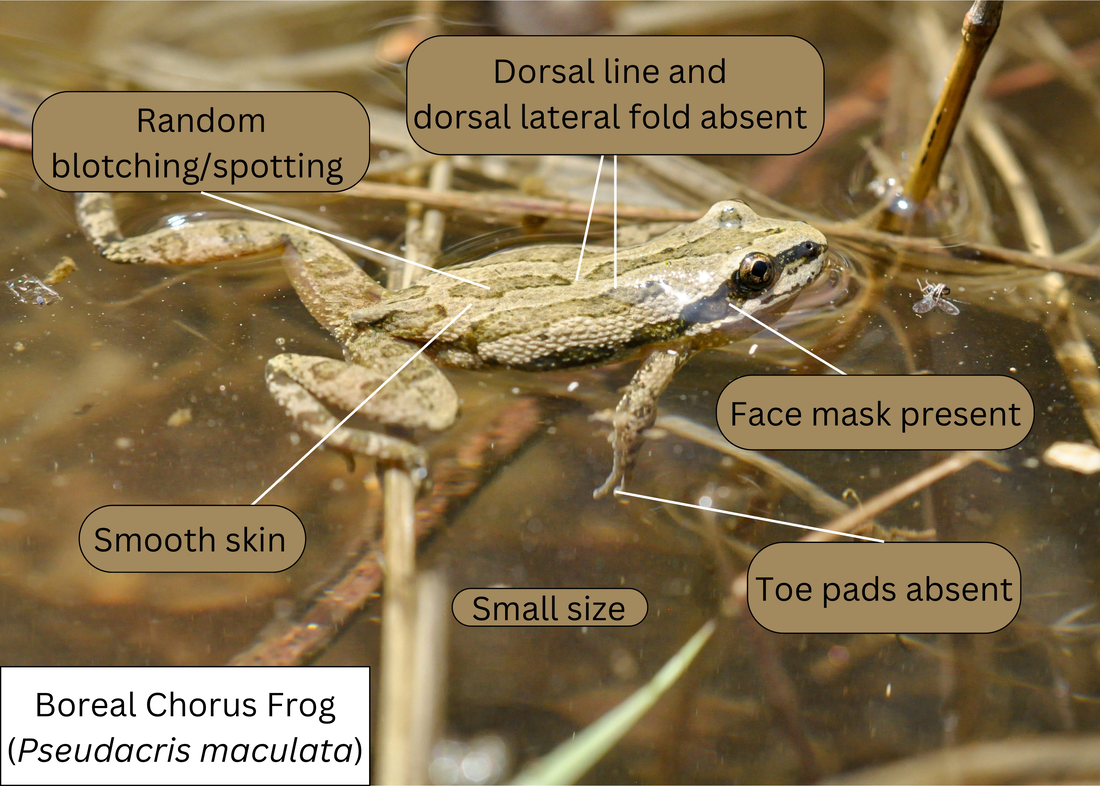

Adult Diagnostic Features

Tadpole Diagnostic Features

Coloration / Markings

Size: Adults are sexually dimorphic, with females lacking a vocal sac for calling and being generally larger (3-5 cm) than males (2.5-4 cm) in snout to vent length (SVL). Tadpoles are 1-5 cm from snout to tail tip. Chorus frogs metamorphose at about 1.5-2.5 cm SVL, with no sexually distinguishing characteristics until 1 to 2 years of age (Amburgey, personal observation). Higher elevation animals are markedly larger than lower elevation individuals.

Habitat: These frogs are common to a wide range of waterbodies including urban, rural, and mountain ponds, flooded meadows, backwaters along streams, and cattle ponds (Hammerson, 1999). Breeding usually occurs in shallow, grassy or reedy ponds that lack fish predators and have no current. Larger ponds and lakes may be utilized if grassy edges are available (see Hammerson, 1999; Amburgey et al., in review for more about habitat selection). Adults, juveniles, and newly metamorphosed individuals may emigrate from breeding ponds to flooded meadows in order to feed in late summer. They can be found at elevations from 1,066 m (3,500 ft) up to 3,670 m (12,000 ft) in Colorado (Hammerson, 1999).

Activity: Breeding activity primarily occurs from nightfall until early dawn. Male calling generally begins in spring (late March to mid May) at low elevation and early summer (late May to early June) at higher elevations (Hammerson, 1999; Amburgey, personal observation). Males may continue to call throughout the summer season even after breeding has occurred. Females are present at breeding sites for shorter duration than males. Animals hibernate between October and March.

Reproduction: Eggs are dark, small (approx. 1mm in diameter) and laid in multiple, loose groups attached to pond vegetation. One female can lay anywhere from 500-2000 eggs in total (Amburgey, personal observation). Tadpoles hatch within a week of fertilization and reach sizes of approximately 3-4 cm before metamorphosis (Amburgey, personal observation). Low elevation animals generally will metamorphose from late June to early July with higher elevation animals metamorphosing as late as September.

Feeding & Diet: Post-metamorphic animals are insectivorous while tadpoles are herbivorous. Tadpoles primarily scrape algae off surfaces while post-metamorphic animals eat small invertebrates such as crickets, beetles, ants, and spiders. Newly metamorphosed animals consume smaller prey such as waxwings, springtails, and midges.

Defenses from Predation: Boreal chorus frogs are not toxic and lack defenses, instead relying on predator avoidance. Adults are primarily active at night when detection is more difficult, and coloration and patterning allows for camouflaging in the boreal chorus frog’s grassy habitats (Matthews, 1971). Males will cease calling when disturbed. Tadpoles may use sudden bursts of speed in order to flee predators. Both adults and tadpoles will dive to the bottom of ponds to hide under decaying vegetation and mud when startled.

Colorado Distribution: Boreal chorus frogs can be found throughout much of the state. Occurrence becomes patchier to the southeast corner of the state (after Hammerson 1999, Shipley & Reading 2006, and Colorado Parks & Wildlife).

Conservation Status: Designated as a Non-game Species in Colorado. Please click here for Colorado regulations regarding this species (see Article I, specifically number 6). NatureServe rank: G5 (Globally Secure), S5 (State Secure). General threats to conservation include habitat loss and fragmentation along with introduction of invasive fish and bullfrogs.

Adult Diagnostic Features

- Small frog with slender limbs

- No toe pads and little webbing between toes of rear feet

- Smooth skin lacking bumps and dorsolateral folds

- Male call is a high ‘preeep’ sound that ascends in pitch, much like a fingernail being dragged over a comb edge (see audio file of call at top of page)

Tadpole Diagnostic Features

- Small tadpole with highly arched tail fin

- Olive to dark brown/black in dorsal color

- Ventral side is golden in color and coiled intestine is visible

- Eyes on outside margin of head

- 2 rows of teeth on upper jaw, 3 rows on lower jaw

Coloration / Markings

- Dark brown, green, black or red stripes extending from the eyes down the sides of the body to or nearly to the groin

- Brown, green, black, red, or grey stripes, spots, or broken stripes on a grey, brown, green or red background on the dorsum

- Mature males have greenish/yellowish throats with loose skin whereas females have smooth, cream-colored throats

- Individuals at higher elevations are generally larger and have more variability in dorsal color

Size: Adults are sexually dimorphic, with females lacking a vocal sac for calling and being generally larger (3-5 cm) than males (2.5-4 cm) in snout to vent length (SVL). Tadpoles are 1-5 cm from snout to tail tip. Chorus frogs metamorphose at about 1.5-2.5 cm SVL, with no sexually distinguishing characteristics until 1 to 2 years of age (Amburgey, personal observation). Higher elevation animals are markedly larger than lower elevation individuals.

Habitat: These frogs are common to a wide range of waterbodies including urban, rural, and mountain ponds, flooded meadows, backwaters along streams, and cattle ponds (Hammerson, 1999). Breeding usually occurs in shallow, grassy or reedy ponds that lack fish predators and have no current. Larger ponds and lakes may be utilized if grassy edges are available (see Hammerson, 1999; Amburgey et al., in review for more about habitat selection). Adults, juveniles, and newly metamorphosed individuals may emigrate from breeding ponds to flooded meadows in order to feed in late summer. They can be found at elevations from 1,066 m (3,500 ft) up to 3,670 m (12,000 ft) in Colorado (Hammerson, 1999).

Activity: Breeding activity primarily occurs from nightfall until early dawn. Male calling generally begins in spring (late March to mid May) at low elevation and early summer (late May to early June) at higher elevations (Hammerson, 1999; Amburgey, personal observation). Males may continue to call throughout the summer season even after breeding has occurred. Females are present at breeding sites for shorter duration than males. Animals hibernate between October and March.

Reproduction: Eggs are dark, small (approx. 1mm in diameter) and laid in multiple, loose groups attached to pond vegetation. One female can lay anywhere from 500-2000 eggs in total (Amburgey, personal observation). Tadpoles hatch within a week of fertilization and reach sizes of approximately 3-4 cm before metamorphosis (Amburgey, personal observation). Low elevation animals generally will metamorphose from late June to early July with higher elevation animals metamorphosing as late as September.

Feeding & Diet: Post-metamorphic animals are insectivorous while tadpoles are herbivorous. Tadpoles primarily scrape algae off surfaces while post-metamorphic animals eat small invertebrates such as crickets, beetles, ants, and spiders. Newly metamorphosed animals consume smaller prey such as waxwings, springtails, and midges.

Defenses from Predation: Boreal chorus frogs are not toxic and lack defenses, instead relying on predator avoidance. Adults are primarily active at night when detection is more difficult, and coloration and patterning allows for camouflaging in the boreal chorus frog’s grassy habitats (Matthews, 1971). Males will cease calling when disturbed. Tadpoles may use sudden bursts of speed in order to flee predators. Both adults and tadpoles will dive to the bottom of ponds to hide under decaying vegetation and mud when startled.

Cited & Additional Resources

Amburgey, S.A., Bailey, L. L., Murphy, M., Muths, E., and W. C. Funk. In review. The effects of hydroperiod and predator communities on amphibian occupancy. Landscape Ecology.

Amburgey, S.A., Murphy, M., and W.C. Funk. In review. Phenotypic plasticity in developmental rate insufficient to offset high tadpole mortality in rapidly drying ponds. Oecologia.

Amburgey, S. A., Funk, W. C., Murphy, M. and E. Muths. 2012. Effects of hydroperiod duration on survival, developmental rate, and size at metamorphosis in Boreal Chorus frog tadpole (Pseudacris maculata). Herpetologica 68:456-467.

Colorado Parks & Wildlife. Natural Diversity Information Source. http://ndis.nrel.colostate.edu/wildlifespx.asp?SpCode=020190. [accessed Feb. 2013].

Corn, P. S., Hossack, B. R., Muths, E., Patla, D. A., Peterson, C. R., and A. L. Gallant. 2005. Status of amphibians on the Continental Divide: surveys on a transect from Montana to Colorado, USA. Alytes 22:85-94.

Corn, P.S., and E. Muths. 2002. Variable breeding phenology affects the exposure of amphibian embryos to ultraviolet radiation. Ecology 83:2958-2963.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. 2nded. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado.124 pp.

Lemmon, E. M., Lemmon, A. R., Collins, J. T., Lee-Yaw, J. A., and D. C. Cannatella. 2007. Phylogeny-based delimitation of species boundaries and contact zones in trilling chorus frogs (Pseudacris). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44:1068-1082.

Matthews, T. C. 1971.Genetic changes in a population of Boreal Chorus frogs (Pseudacris triseriata) polymorphic for color.American Midland Naturalist 85:208-221.

Moriarty, E. C. and D. C. Cannatella. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of North American chorus frogs (Pseudacris). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30:409-420.

Scherer, R. D., Muths, E., and B. R. Noon. 2012. The importance of local and landscape-scale processes to the occupancy of wetlands by pond-breeding amphibians. Population Ecology 54:487-498.

Spencer, A. W. 1964. The relationship of dispersal and migration to gene flow in the boreal chorus frog. PhD Dissertation. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Co, New York, New York. 219 pp.

Tordoff , W., III, and D. Pettus. 1977. Temporal stability of phenotypic frequencies in Pseudacris triseriata (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae). Journal of Herpetology 11:161-168.

Tordoff, W., III, Pettus, D., and T. C. Matthews. 1976. Microgeographic variation in gene frequenices in Pseudacris triseriata (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae). Journal of Herpetology 10:35-40.

Amburgey, S.A., Bailey, L. L., Murphy, M., Muths, E., and W. C. Funk. In review. The effects of hydroperiod and predator communities on amphibian occupancy. Landscape Ecology.

Amburgey, S.A., Murphy, M., and W.C. Funk. In review. Phenotypic plasticity in developmental rate insufficient to offset high tadpole mortality in rapidly drying ponds. Oecologia.

Amburgey, S. A., Funk, W. C., Murphy, M. and E. Muths. 2012. Effects of hydroperiod duration on survival, developmental rate, and size at metamorphosis in Boreal Chorus frog tadpole (Pseudacris maculata). Herpetologica 68:456-467.

Colorado Parks & Wildlife. Natural Diversity Information Source. http://ndis.nrel.colostate.edu/wildlifespx.asp?SpCode=020190. [accessed Feb. 2013].

Corn, P. S., Hossack, B. R., Muths, E., Patla, D. A., Peterson, C. R., and A. L. Gallant. 2005. Status of amphibians on the Continental Divide: surveys on a transect from Montana to Colorado, USA. Alytes 22:85-94.

Corn, P.S., and E. Muths. 2002. Variable breeding phenology affects the exposure of amphibian embryos to ultraviolet radiation. Ecology 83:2958-2963.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. 2nded. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado.124 pp.

Lemmon, E. M., Lemmon, A. R., Collins, J. T., Lee-Yaw, J. A., and D. C. Cannatella. 2007. Phylogeny-based delimitation of species boundaries and contact zones in trilling chorus frogs (Pseudacris). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 44:1068-1082.

Matthews, T. C. 1971.Genetic changes in a population of Boreal Chorus frogs (Pseudacris triseriata) polymorphic for color.American Midland Naturalist 85:208-221.

Moriarty, E. C. and D. C. Cannatella. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of North American chorus frogs (Pseudacris). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30:409-420.

Scherer, R. D., Muths, E., and B. R. Noon. 2012. The importance of local and landscape-scale processes to the occupancy of wetlands by pond-breeding amphibians. Population Ecology 54:487-498.

Spencer, A. W. 1964. The relationship of dispersal and migration to gene flow in the boreal chorus frog. PhD Dissertation. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Co, New York, New York. 219 pp.

Tordoff , W., III, and D. Pettus. 1977. Temporal stability of phenotypic frequencies in Pseudacris triseriata (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae). Journal of Herpetology 11:161-168.

Tordoff, W., III, Pettus, D., and T. C. Matthews. 1976. Microgeographic variation in gene frequenices in Pseudacris triseriata (Amphibia, Anura, Hylidae). Journal of Herpetology 10:35-40.

| Amburgey_etal_2012_Herpetologica.pdf |

Account compiled by: Staci Amburgey

Reviewed by: Lauren Livo and Brad Lambert

Last updated: 4/14/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Suggested Citation

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2014. Species account for Boreal chorus frog (Pseudacris maculata). Compiled by Staci Amburgey. http://www.coparc.org/colorado-amphibians---boreal-chorus-frog.html [accessed date here].

Reviewed by: Lauren Livo and Brad Lambert

Last updated: 4/14/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Suggested Citation

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2014. Species account for Boreal chorus frog (Pseudacris maculata). Compiled by Staci Amburgey. http://www.coparc.org/colorado-amphibians---boreal-chorus-frog.html [accessed date here].