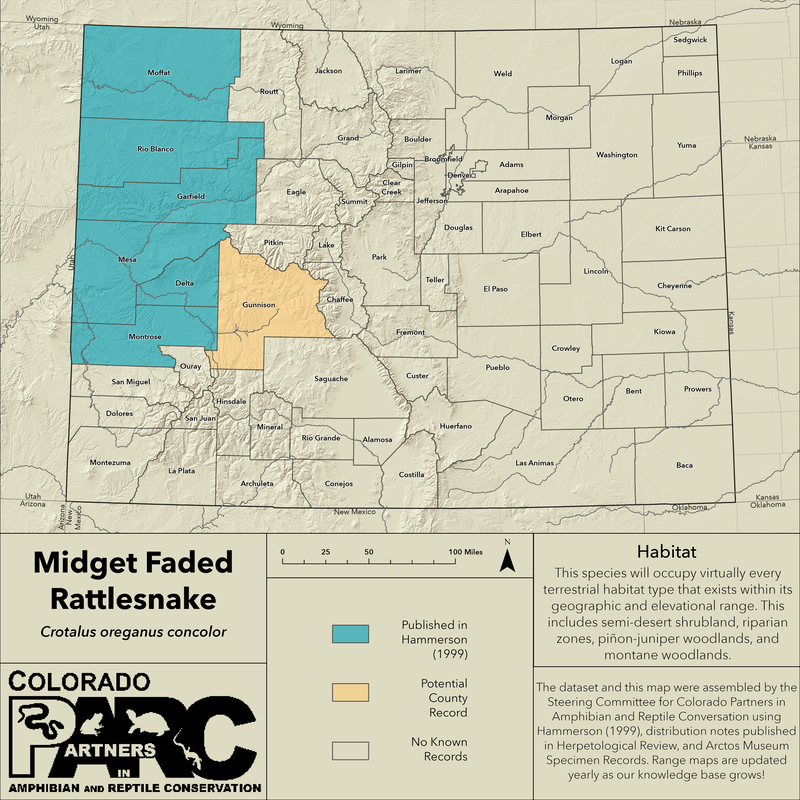

Distribution: The Midget Faded Rattlesnake is only found within the Green River formation of Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming. This species is found below 7,000 ft in elevation.

(Hammerson, 1999)

(Hammerson, 1999)

Habitat: In Wyoming, C. concolor habitat consists of high, cold desert dominated by sagebrush (Astemesia spp.) and with an abundance of rocky outcrops and exposed canyon walls. Greasewood (Sarcobatus vermiculatus), juniper (Juniperus scopulorum), and other woody plants occur secondarily, or occasionally as co-dominants or even dominants, in some areas. Juniper woodlands are more common at higher altitudes. (Travsky & Bovias, 2004) In Colorado, this species will occupy virtually every terrestrial habitat type that exists within its geographic and elevational range. This includes semi-desert shrubland, riparian zones, piñon-juniper woodlands, and montane woodlands. (Colorado Parks and Wildlife)

Activity: The active season for these snakes is shorter than for most rattlesnakes, as the warm season is short, with the winters being long and cold. Midget Faded Rattlesnakes emerge from hibernation in April or May, depending on the year. Dispersal from hibernacula doesn’t occur for 2-3 weeks after initially emerging. Snakes return to hibernacula in October or early November. Adult male and non-gravid female Midget Faded Rattlesnakes disperse around 2,000 meters from the hibernacula. They have some of the largest activity ranges and longest migrations of any rattlesnake species. Gravid females, post-partum females, and juveniles do not disperse much at all from their hibernacula, with females often dispersing less than 20 meters from the den site. (Travsky & Bovias, 2004)

Size: Midget Faded Rattlesnakes are the smallest member of the Crotalus oreganus complex. A typical adult is around 24 inches in length, but some may reach lengths of up to 30 inches. They are sexually dimorphic, with males reaching larger sizes than females do.

Conservation Status: The Midget Faded Rattlesnake is listed by Colorado Parks and Wildlife as a Species of Special Concern. As with most rattlesnakes, the greatest threat to their well being is that posed by humans. While this species is listed, anyone may kill a rattlesnake to protect life or property. Ironically, most bites on humans occur while the snake is being harassed or killed. (Hammerson, 1999)

Reproduction: In Wyoming, breeding generally occurs following emergence in early May. Gravid females give birth to live young from mid August into September. 3-4 individuals is most common, but clutch size rarely ranges to 7 individuals. Gestation occurs solitarily or in an aggregation of other females. Triennial breeding (occuring every three years) is most common, but biennial and quadrennial also occur. Parturition dates generally are earlier for Midget Faded Rattlesnakes that experience lower mean temperature environments.

Feeding & Diet: Midget Faded Rattlesnakes mostly feed on small mammals and lizards. Adults will take larger food items and their diet may also include birds. Adults tend to hunt and feed in the evening and at night. Juveniles hunt during the daytime hours because they lose body heat much faster after the sun goes down. (Hammerson 1999)

Defenses from Predation: Midget Faded Rattlesnakes are extremely peaceful snakes and will only react defensively if disturbed or spooked. Upon being disturbed, the snake will assume a defensive posture by picking the head up off of the ground. As with all rattlesnakes, the snake will rattle the tail in an attempt to alert and ward off a possible predator. A snake will always prefer to flee from an encounter if possible, but if the snake feels threatened enough, it will strike. The venom belonging to Midget Faded Rattlesnakes is among the most lethal of all Crotalus species. It is composed of both a potent neurotoxin and a potent myotoxin. (Keyler et al, 2020)

Cited & Additional Resources

Ernst, C. H., and E. M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Books, Washington and London. 167 pp.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. 2nd ed. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado. 364 pp.

Pyron, R. A. and F. T. Burbrink. 2009. Systematics of the Common Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula; Serpentes: Colubridae) and the burden of heritage in taxonomy. Zootaxa 2241:22-32.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, New York. 362 pp.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and reptiles in Colorado. 2nd ed. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado. 364 pp.

Pyron, R. A. and F. T. Burbrink. 2009. Systematics of the Common Kingsnake (Lampropeltis getula; Serpentes: Colubridae) and the burden of heritage in taxonomy. Zootaxa 2241:22-32.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, New York. 362 pp.

Account compiled by: Graham Zephirin

Reviewed by: Rémi Pattyn

Last updated: 4/11/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Reviewed by: Rémi Pattyn

Last updated: 4/11/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Suggested Citation

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2021. Species account for Midget Faded Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus concolor). Compiled by Graham Zephirin. http://www.coparc.org/[accessed date here]. Editors: Rémi Pattyn.

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2021. Species account for Midget Faded Rattlesnake (Crotalus oreganus concolor). Compiled by Graham Zephirin. http://www.coparc.org/[accessed date here]. Editors: Rémi Pattyn.