Western CoachwhipMasticophis flagellum testaceus

NON-VENOMOUS |

|

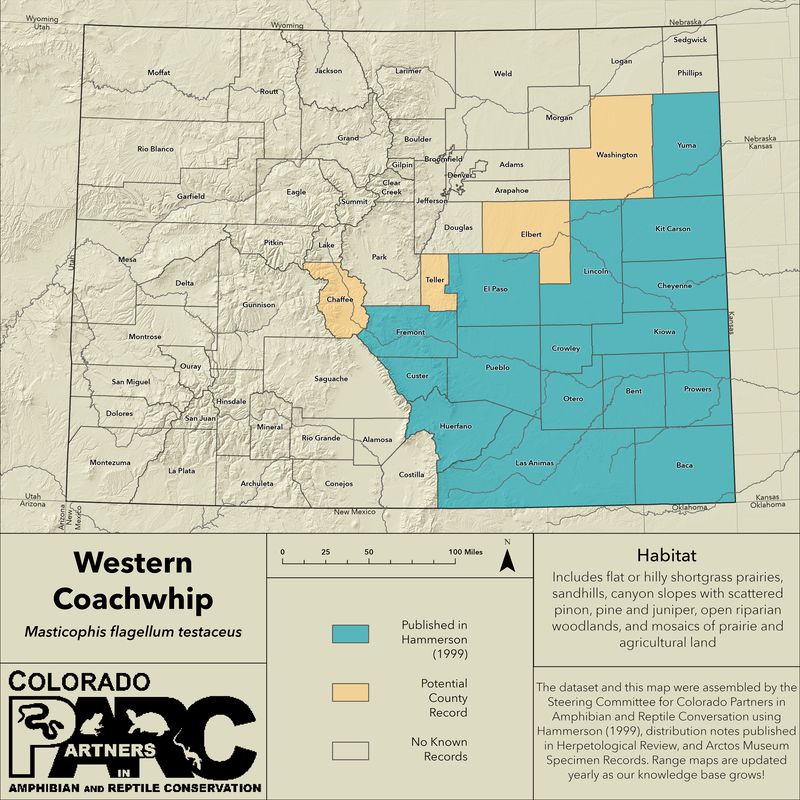

Distribution: The Coachwhip ranges from southeastern North Carolina, through peninsular Florida, west to Nebraska, eastern Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, southern Utah and Nevada, and mid- and southern California. They also occur southward into Mexico (Ernst & Ernst 2003).

Found in southeastern Colorado, usually below 6,000 feet in elevation. However, the Coachwhip has been found at elevations of up to 7,700 feet in the Wet Mountains in Custer County. Also, in the Republican River drainage in northeastern Colorado Coachwhips are found at elevations of 3,000 to 4,000 feet (Hammerson 1999). Habitat: In Colorado, habitat for this species includes flat or hilly shortgrass prairies, sandhills, canyon slopes with scattered pinon, pine and juniper, open riparian woodlands, and mosaics of prairie and agricultural land (Hammerson 1999). Coachwhips can also be found in dry grasslands, savannahs, scrublands, or deserts (Stebbins 2003). Elsewhere, they have been found to prefer chaparral, mesquite-creosote brush, thornbush, pine and palmetto flatwoods, and pine-juniper and oak woodlands. Coachwhips use the scattered vegetation and leaf litter for both foraging and escape defense behavior. The soils that a Coachwhip is found on can vary from loose sand to solid loam. Rocks do not need to be present for this species to persist (Ernst and Ernst 2003). Some Coachwhips may occasionally spend the night in vegetation aboveground when conditions are warm enough.

|

Diagnostic Features

Size: The total body length (TBL) of a Coachwhip is up to 259 cm (102 in) but most individuals range in size from 100-150 cm (39-59 in), making it a very long snake. Males have a tail length (TL) that consists of 22-28% of their TBL while females have a TL of 21-26% of their TBL. The hatchlings are about 21 to 41 cm long.

|

Activity: The Coachwhip is a diurnal species, often seen foraging in the hottest hours of a summer day. When foraging, the Coachwhip holds its head vertically, high above the ground, and it can prowl at a rate of 0.30 mph (0.5 kph) and a maximum speed of 3.7 mph (6.0 kph; Ernst & Ernst 2003). Their speed is associated with their unusually long major axial muscle units. Their activity is not restricted to the ground because C. flagellum has the ability to climb into shrubs and low trees to bask or forage. Most of the basking that Coachwhips do occurs in the morning across all active seasons, possibly staring in March, but most often beginning in April or early May. Across most of its range, this species remains active until September to November. To escape severe summer heat, C. flagellum will retreat to underground animal burrows. Little is known about the burrowing behavior of this species. Reports from Georgia found Coachwhips hibernating in tunnels formed by the decay of pine roots on dry hillsides, and in Kansas, Coachwhips have been found hibernating in deep rock crevices on hillsides or in small mammal burrows on the prairies. In southern California and likely in Colorado, hibernation sites include abandoned rodent burrows or spaces under old buildings (Ernst & Ernst 2003).

Conservation Status: Designated as a Non-game Species in Colorado. A Scientific Collection Permit from Colorado Parks & Wildlife is required to capture or handle this species (see State of Colorado regulations here). NatureServe rank: G5 (Globally Secure), S5 (State Secure). Habitat elimination has been caused by intensive agricultural development. Still, the Coachwhip remains throughout most of its historical range in Colorado because it tolerates moderate habitat alterations typical of rural plains communities (Hammerson 1999). Combined with its large size, the habit of C. flagellum to bask on warm roads makes it vulnerable to traffic. Furthermore, in rural areas, some Coachwhips are killed by humans who view them as a threat to their chickens (Hammerson 1999).

Reproduction: Adults most likely mature at a TBL of 70 to 90 cm (28 to 35 in) and mating occurs in late spring in Colorado (Ernst & Ernst 2003). Based on observations, females seem to not breed any earlier than their third spring, though this is still uncertain. Copulation has been observed from late April to late May in Texas and New Mexico but no study on the sexual cycle of this species has been reported. In Colorado and nearby areas, Coachwhips lay clutches of about 14-18 white, leathery eggs between mid-June and mid-July. The eggs are laid in loose soil at depths of up to 30 cm below the surface. Eggs are also laid in rotting logs, decaying plant matter, or in animal burrows. Hatching occurs in late August to early September.

Feeding & Diet: C. flagellum is an active forager looking for prey and predators, often with its head and neck well above the ground (Stebbins 2003). When prey is discovered, the Coachwhip will then pursue, seize, and quickly swallow it. Because it has a long and slender body form, a Coachwhip can follow its prey target into narrow crevices and burrows. Its foraging is not restricted to ground or below-ground prey because C. flagellum will also climb in trees to raid bird’s nests. To catch swift lizards, the Coachwhip will assume a “sit and wait” position to ambush its prey (Ernst & Ernst 2003). Coachwhips are opportunistic foragers and because of this and their relatively large home ranges, they come in contact with many small animals (Hammerson 1999). Some of their prey include insects such as grasshoppers and cicadas; amphibians such as spadefoots and frog eggs; reptiles such as turtles, lizards, and other snakes; birds, including adults, nestlings, and eggs; and mammals such as bats, shrews, jackrabbits, cottontails, wood rats, mice, and ground squirrels (Ernst & Ernst 2003).

Defenses from Predation: The natural enemies of the Coachwhip include various carnivorous mammals, raptors, Greater Roadrunners, and other snakes. Hawks may be the most commonly-observed predator of C. flagellum. Traffic also claims the lives of many Coachwhips each year, along with wildfires and possibly insecticide sprays. To avoid predators, C. flagellum will quickly crawl away and often will move into trees or bushes in order to escape. If trapped, a Coachwhip will often strike and bite its attacker vigorously, often aiming for the face. When handled, this species will thrash about, spray musk and fecal matter and bite its holder. Some Coachwhips will feign death by cocking the head and eyes downward, opening the mouth, and partially extending the tongue (Ernst & Ernst 2003).

Cited & Additional Resources

Ernst, C. H., and E. M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Books, Washington and London. 198 pp.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and Reptiles in Colorado. 2nd ed. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado. 325 pp.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, New York. 352 pp.

Hammerson, G. A. 1999. Amphibians and Reptiles in Colorado. 2nd ed. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado. 325 pp.

Stebbins, R. C. 2003. Western reptiles and amphibians. 3rd ed. Houghton Mifflin Company, New York, New York. 352 pp.

Account compiled by: Beth Wittmann

Reviewed by: Lauren Livo (text & map)

Last updated: 4/14/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Reviewed by: Lauren Livo (text & map)

Last updated: 4/14/2022 by Rémi Pattyn

Suggested Citation

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2014. Species account for Western Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum testaceus). Compiled by Beth Wittmann. http://www.coparc.org/coachwhip.html [accessed date here]. Editor: Lauren Livo.

Colorado Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation. 2014. Species account for Western Coachwhip (Masticophis flagellum testaceus). Compiled by Beth Wittmann. http://www.coparc.org/coachwhip.html [accessed date here]. Editor: Lauren Livo.